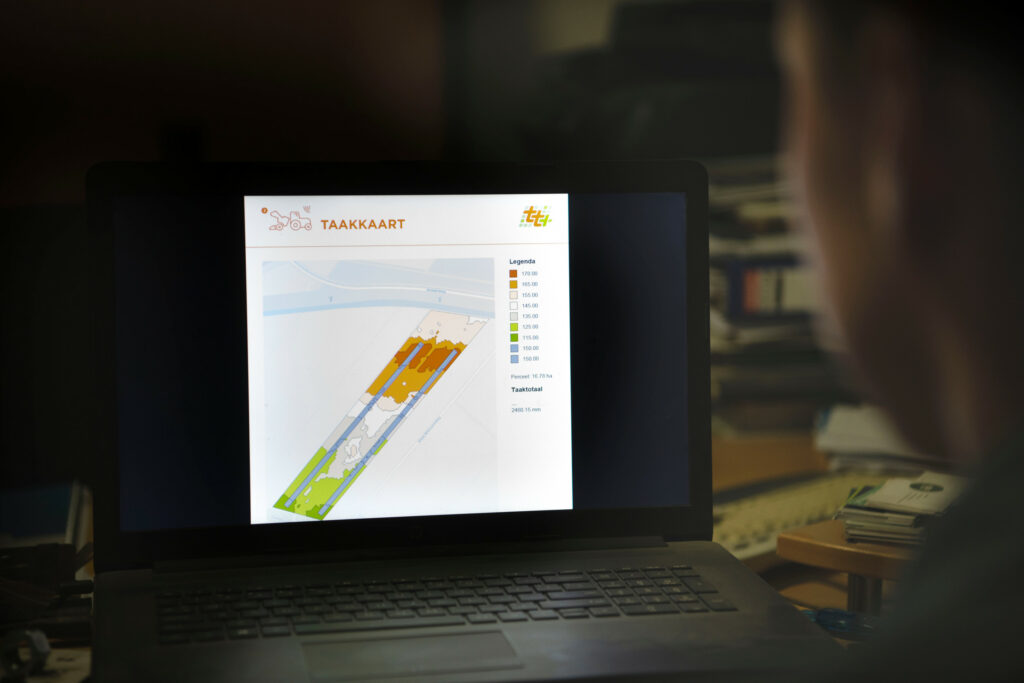

Variable seeding with task maps is not yet common practice

To what extent do Dutch arable farmers today vary their seeding and planting distances based on a task map? We posed this specific question to around ten manufacturers and suppliers of seeders and planters, resulting in some noteworthy insights.

Technically, it’s no longer a challenge: varying seeding density during the sowing of maize, carrots, sugar beets, onions, and other (vegetable) crops based on a task map is feasible. Potato planters can often adjust the spacing between the seed potatoes as well. But is this being done in practice? Here’s what suppliers observe.

In maize, it’s barely a topic

When sowing maize, varying the seeding distance is rare or non-existent. This is partly because the crop is usually used for livestock feed, and maize is often grown on light soil. Adjusting the seeding density to the soil condition or yield potential doesn’t offer the added value (in terms of dry matter or starch yield) that livestock farmers seek to recoup the additional costs that a contractor might charge. “Moreover,” says Erwin Tessers of Amazone importer Kamps de Wild, “maize seed isn’t the most expensive. Sowing less per hectare doesn’t significantly reduce costs. I do notice interest in the technology, but it’s more with an eye toward the future.”

Rick de Groot of Kverneland Benelux sees some customers making adjustments in seeding density. “I hear of more seeds being sown per hectare on a high (and dry) sandy area to cover that part properly and reduce weed pressure. Sometimes it’s also said that denser seeding of maize produces a crop that’s less susceptible to wind damage. And I also hear arguments about more uniform ripening: more seeds per hectare in poor, dry spots so the plants face more competition, grow slower, and ripen earlier.”

According to Hans Hoogland of Lemken, there’s minimal demand for maize seeding using a task map. “The need and necessity are low. Contractors often don’t get compensated for the additional costs. What helps, though, is that seed suppliers offer (free) tools that can create a task map based on soil type or satellite images from previous years’ crops.”

Monosem importer Farmstore and Kuhn importer Reesink Agri note that task maps are gradually being used for varying seeding distances. “One of the main reasons for a contractor to purchase an electrically driven maize seeder is to avoid changing chains when altering the number of seeds per hectare,” says Christiaan Borkus of Reesink.

Text continues below picture

Somewhat in sugar beets

Farmstore and Kverneland observe cautious interest from arable farmers and contractors in varying seeding distances for sugar beets. Rick de Groot hesitates to give a percentage, while Chris van de Lindeloof from Farmstore estimates that about 2% of farmers and contractors currently apply this. “In the Netherlands, we are too focused on the technology, which no longer poses a challenge. Your strategy is much more important. Do you use the yield potential of a field for a more uniform (ripening) crop, or are you aiming for maximum yield? Your strategy determines where you sow thicker or thinner and where you apply more or less fertilizer. Keep it simple and stick to your goals.”

Despite having the same cultivation goal, strategies can differ, as was evident last year during visits to participants in the The National Fieldlab for Precision Farming (NPPL) project. Some sow more densely in areas with lower yield potential, while others sow more sparsely.

De Groot cites uniformity as a strategy. “In sugar beets, and also in potatoes, it’s common to sow and plant more densely next to tramlines or wheel tracks for a more uniform crop. On the one hand, this compensates for the yield loss from unsown or unplanted potatoes, while on the other hand, it takes advantage of the reduced competition and increased light exposure. However, you don’t need a task map for that. Any standard seeder or planter can do it.”

Text continues below picture

Hesitant in onions

According to technology suppliers, many onion growers are still hesitant to vary seeding distances for seed onions. De Groot says, “Like with seed potatoes, the size and sorting of onions are crucial for classification and payment. Uniformity is key, although I’ve seen cases where denser seeding is done in areas with higher organic matter to avoid overly large onions. I’ve also seen farmers divide a field with varying soil types into two parts and plant two different varieties with corresponding seeding distances.” Van de Lindeloof sees potential in adjusting seeding distances based on soil texture or heaviness. “One of our customers is experimenting with thinner seeding on light soil and denser seeding on heavier soil.”

Even less in other (vegetable) crops

“In a crop like carrots, you could easily apply the same strategy as in onions,” continues Van de Lindeloof. “I personally sow my peas variably using a task map, with the yield potential of a field as the basis. I determine this partly based on satellite images of the green manure during winter. Green manure is the most honest crop in that regard since it isn’t fertilized. A higher yield potential means denser sowing, as peas are paid based on their hardness.” De Groot adds, “We see little enthusiasm for variable seeding in other vegetable crops like carrots and red beets.”

5 to 10% of potato planting is variable

Varying planting distances for potatoes happens to a limited extent. Kristof De Ruyck of AVR says, “We barely see it happening based on soil conditions.”

At Dewulf, Christiaan Poot sees growers with varied fields and expensive land actively working on it. “I think 3 to 5% of our customers plant more sparsely on light soil and more densely on heavier soil. I also see a few planting more sparsely along tree lines where the tubers grow less due to lack of sunlight, saving on seed potatoes.”

“I had expected a larger uptake,” says Arent Lanenga of Grimme. “I estimate that less than 10% of our customers vary planting distances based on yield data from a previous crop. You need to see the added value compared to the costs of the technology and creating a task map.”

Text continues below picture