Tinkerer revives old RTK GPS system

With the phasing out of 2G and 3G networks, older GPS systems often no longer receive RTK correction signals. Outdated modems simply cannot handle the newer networks. Bart de Reu had a eureka moment: why not just use your phone’s internet connection? That is how the dairy farmer and computer technician began developing his own modem: the Bacom RTK.

Most telecom providers have discontinued their 3G networks in favor of 4G and 5G. As a result, older GPS systems now rely on the (overloaded) 2G network to receive an RTK correction signal.

If you are still using such a system, you have probably been offered a trade-in deal to replace your GPS with a brand-new system. So was Bart de Reu, based in Aalter, near Ghent. But the price was too steep for him. “For me, the GPS system is more of a luxury than a necessity,” the farmer explains.

De Reu milks 120 cows and does most of the fieldwork himself. While planting corn and streaming music from his phone, he had a flash of insight. De Reu: “My phone receives 5G, and I always have it with me. Why not use that signal? I just needed to build a bridge.” And so he did.

Read more below the photos

Internet connection required for RTK signal

Besides dairy farming, De Reu is passionate about computer technology. He runs his own IT company as a side business, developing custom software and automation solutions, primarily for agricultural clients. But developing his own modem? That was a first.

He explains: “The GPS system uses satellites to determine its location, but that’s not very precise. If you want centimeter accuracy, you need an additional RTK correction signal. That signal is essentially a network of fixed base stations in the region. But to receive that RTK signal, you need an internet connection,” De Reu says. “And that is where the problem lies: old modems cannot handle 4G or 5G. Since 3G is being phased out, they fall back on the already overloaded 2G network—at least while it still exists.”

Bridge between GPS receiver and mobile phone

Over the past few years, GPS system providers have traded in as many outdated systems as possible. Sometimes you can buy a new modem that supports 4G. But Bart de Reu developed his own solution: a bridge between the GPS receiver and a mobile phone. “I think it is ideal. You always have the latest technology with you. And it’ll continue to work—even when 6G arrives.” According to De Reu, the system can also connect to a Starlink Mini receiver, which is useful in regions with little or no internet reception.

Why do GPS system manufacturers not use this smartphone-based internet solution by default? Industry insiders say it’s mainly due to reliability: if the phone is used for internet, the signal might temporarily degrade when a call comes in. It is also difficult to offer global support with so many phone models in use. Some manufacturers do use this approach in areas with poor coverage but view it as a last resort.

Bacom RTK system developed

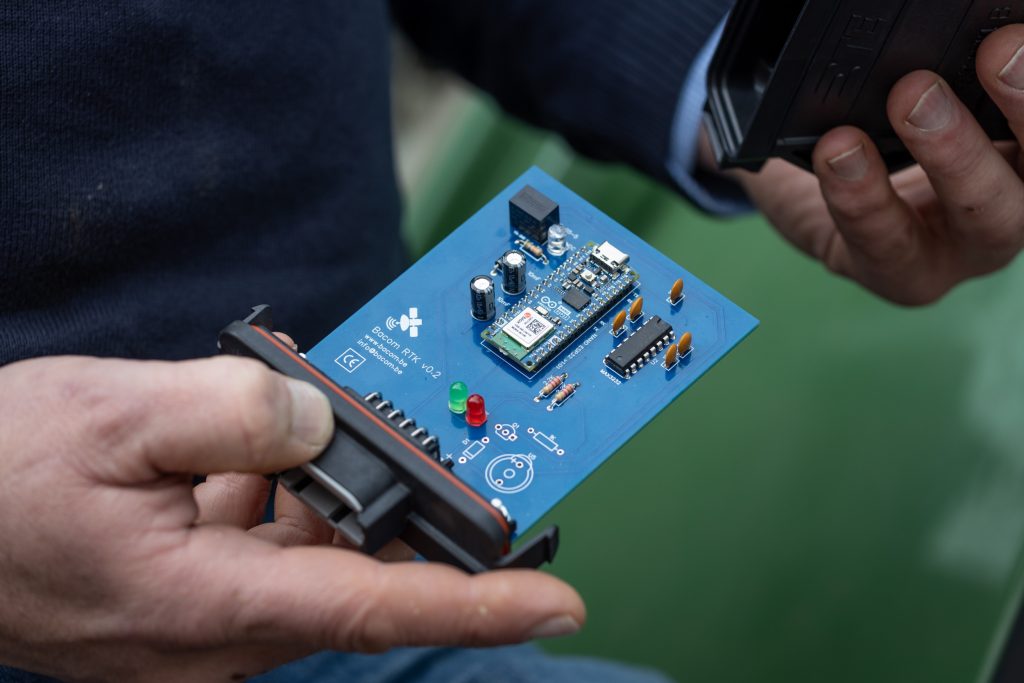

De Reu shows off his modem on the tractor he uses on his farm: a Fendt 718 Vario. The GPS receiver is integrated into the roof hatch. Now, right next to the receiver sits the Bacom RTK—De Reu’s own invention, named as a blend of ‘Bart’ and ‘Computers.’

All he does when getting into the tractor is turn on his phone’s hotspot. The Bacom RTK automatically connects, and within 30 seconds the Fendt screen indicates a signal from an RTK network with an ‘External Base.’ The display promises 2-centimeter accuracy.

Self-programmed

It sounds simple enough, but De Reu put in a lot of work. He used an online tool to design a custom PCB, which he had manufactured elsewhere. Then he soldered all the components himself: from chips and capacitors to voltage regulators and signal converters. The voltage transitions multiple times: from 12 volts (tractor) to 5 volts, then 3.3 volts (for software), and finally to 24 volts (GPS system serial line).

De Reu wrote the software—over 1,500 lines of code—using the open-source Arduino platform, with which he has extensive experience. He then installed the code on a standard ESP32 microcontroller. He purchased the necessary components to build a proper housing and matching cable.

The hardest part, says De Reu, was writing the code to properly relay the RTK signal to the GPS. “The first time I connected it and saw the RTK status on the Fendt screen again, I was over the moon,” he says.

From there, he focused on fine-tuning and adding features, such as adjustable baud rates (data transmission speed) ranging from 9,600 to 115,200. This allows the Bacom RTK to work with various GPS systems. De Reu: “The GPS and modem need to speak at the same speed to understand each other.” The latest feature is remote software updates.

Bacom RTK modem costs €499

De Reu began receiving inquiries from fellow farmers in the area. That prompted him to offer his invention via a webshop (Bacom.be) for €499, including a brand-specific cable, for those with outdated GPS systems.

There are a few requirements. The GPS system must have previously worked with RTK signals—otherwise, an expensive license activation is needed. The GPS receiver (or wiring harness) also needs a free port to connect the Bacom RTK as an external base. It’s wise to have a phone holder and charger in the tractor, as the battery drains quickly with the hotspot on. An unlimited data phone plan is also recommended.

One-time login

The Bacom RTK unit connects via cable to a free port on the receiver. Through this cable, it communicates with the RX and TX lines and receives power. Each unit has a unique QR code, which you scan once with your phone. This opens a login page where you enter your RTK provider’s credentials. You also input the correct baud rate if needed.

Once the hotspot is on, it just works. The connection runs in the background, and when you re-enter the tractor, the API briefly checks the login and settings before establishing a connection—hence the 30-second delay.