Can it be done? Farming without glyphosate

Right now, those in arable farming are watching closely what will happen with banning glyphosate – and wondering how they will manage without it. Here we have a look at what options would remain for weed control.

This herbicide was first marketed by Bayer’s Monsanto as ‘Roundup.’ It does not affect crops that have been genetically-modified to withstand it, but kills many species of weeds that may be growing within the crop. It’s also used to kill weeds nearby to crops, for ‘burn down’ of small weeds before planting, and to desiccate some crops (those not modified to withstand glyphosate) before harvest to improve harvest quality and for other reasons.

Nearly 100,000 lawsuits in the US

Although there have been health concerns for many years related to the use of this substance, restriction on its use have ramped up considerably since 2015 when an agency of the World Health Organization stated that it’s likely to cause cancer. In mid-2020, Bayer settled nearly 100,000 lawsuits in the US (totally almost $ 11 billion USD) focussed on health claims related to Roundup.

Now, glyphosate use is banned in public spaces or otherwise restricted in over 40 countries (one of many lists with specific details can be found here).

Glyphosate banned

At this point, the only country that has completely banned glyphosate is Luxembourg; the ban there took effect at the end of 2020 “notwithstanding its approval at European level until 15 December 2022.” The government of Germany decided this year to completely ban glyphosate by 2024 and in the meantime, German farmers must reduce use.

In agriculture-intensive France, the government had set a complete ban by the end of 2021, but this has been extended. However, the government is granting a temporary tax credit of 2,500€ to farmers who declare this year and/or in 2022 that they’ve stopped using glyphosate. France has also pledged financing to help farmers with getting new equipment they will need to deal with the loss of this herbicide.

Text continues underneath image

The looming question

No one can argue it’s not a billion dollar question – whether or not it’s possible to maintain crop yield without glyphosate. Scientists Hugh Beckie, Ken Flower and Michael Ashworth of the Australian Herbicide Resistance Initiative at the University of Western Australia believe it’s possible, but of course, under certain conditions. In 2020, they published a paper concluding that “model predictions suggest that we can farm profitably without glyphosate by consistently utilizing key non-herbicidal weed management practices combined with robust pre-emergence soil residual herbicide treatments.” However, they add that “maintaining low weed seed banks will be challenging.”

Here are some of the alternative weed control solutions they suggest:

- Using real-time sensors (already used for identifying weed patches in Australia) to do targeted weed control with herbicides like paraquat/diquat, “although they will have limited impact on more established and perennial weeds.” These sensors can be attached to rapid-response, hydraulically-controlled tynes for shallow ‘targeted tillage.’

- Imaging from satellites or drones to map weed patches, followed by site-specific tillage and/or spraying

- Using very high crop seeding rates (even broadcast in weed patches)

- Inter-row tillage

- Reduced harvest height to ensure weed seed interception for reducing weeds the following season

- Soil residual pre-pant herbicides such as trifluralin, triallate, atrazine, prosulfocarb or pyroxasulfone are already commonly applied just before or at seeding to control key weeds, such as annual ryegrass, wild radish and bromegrass

- ‘Dry’ or early seeding with pre-plant soil residual herbicides to allow crops to establish ahead of weeds

- less production of inherently poor weed-competitive pulse crops

Other strategies

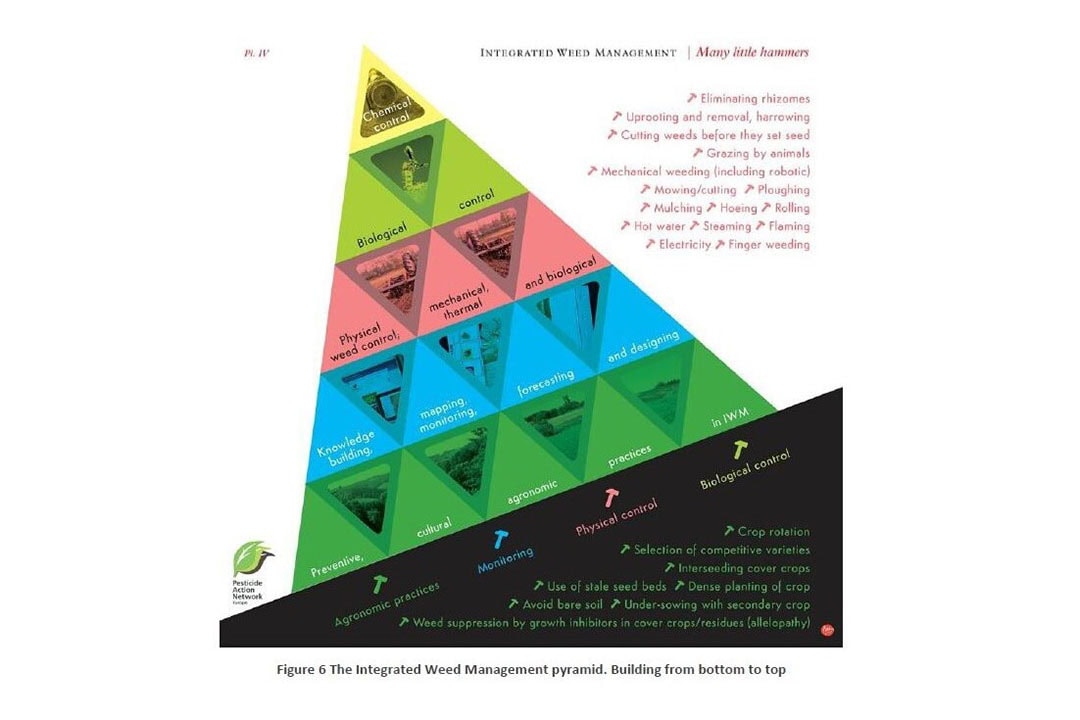

These and other methods are also outlined in a report from the ‘Pesticide Action Network’ Europe, prepared with the assistance of Dr. Isabel Branco. The report stresses that “successful and sustainable weed management systems are those that use integration among techniques rather than depending on a single method, in line with the “many small hammers” approach of integrated weed management.

Text continues underneath image

Here are some other strategies outlined in the document:

- Natural herbicides such as acetic acid, citric acid, clove oil, maize gluten meal and Cinmethylin (produced by some species of sage; kills several annual grasses and suppresses some broad-leaved weed species)

- GPS technology to map weed density

- Future use of specialized weed-killing or removal technology, once commercialized, including infrared radiation, lasers, microwave radiation, ultra-sonic systems, real-time intelligent robotic weed control systems and electricity

However, the report recognizes that hi-tech tools may not be affordable by most small/medium farmers, but “depending on the culture and set-up of farming operations, there may be options to share machinery between farms cooperating together.”

Industry response

When asked about adjusting to a possible future without glyphosate, two European farming associations both mention the importance of using glyphosate with no-till or minimum-till practices. In general, tillage (which can be used to control weeds) causes erosion, requires significant fuel consumption, disturbs soil structure and microbiota, reduces soil moisture retention and releases carbon into the atmosphere.

Indeed, in the event of a ban on the use of glyphosate in Germany, according to farming association Deutscher Bauernverband, “it can be assumed that the proportion of land in Germany that is cultivated with mechanical tillage would increase massively.” Right now in that country, glyphosate is generally only used to control competing weeds before sowing or when reseeding grassland.

We cannot eliminate any existing safe means to combat pest and disease without having a viable immediate and cost-effective alternative available

Copa-Cogeca, which represents European farmers and agri-cooperatives, states that European agriculture currently lacks alternative weed control methods (whether chemical, physical, genetic etc.) that are at least as safe, cost-efficient and widely applicable (both for species and regions) as glyphosate. The organization states that “we cannot eliminate any existing safe means to combat pest and disease without having a viable immediate and cost-effective alternative available. After all, we are talking about huge volumes of agricultural raw materials, cereals, where even small changes in costs make a major impact in the market and economic margins.”

Copa-Cogeca points out that for now, during the current renewal process the AGG of Rapporteur Member States has concluded that glyphosate is still as safe as it was in 2017 when last re-approved at EU level. “We are looking forward now to see the European Food Safety Authority conclusions hopefully early 2022. After those, we will make further assessments.”

Text continues underneath image

Research needed

When asked what research is needed to achieve success growing crops without glyphosate, Beckie and his colleagues in Australia point to the need to integrate various components (such as cultural, mechanical/physical, biological, herbicidal) in various agro-environments such as the US Midwest, Western Australia or Europe.

Beckie adds that “site-specific or precision weed management is still the best route to reduce herbicide (including glyphosate) use by applying herbicides only where and when weeds are present. For example, in fallow (non-crop) fields, herbicide savings of 80-90% have been documented by using optical sprayers, in a ‘green on brown’ application.”

Looking ahead, Beckie believes that glyphosate use in various countries, whether it continues as it is now, is restricted in some fashion or banned, will largely be decided by politics and the international grains trade. “That is, maximum pesticide residue levels in grain, societal pressure, etc..” he says.

Join 17,000+ subscribers

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated about all the need-to-know content in the agricultural sector, two times a week.